‘He lies on the beach. The waves lap around his head. A small trickle of blood pours out of the hole in his temple. He’s dead.’ Extract from Mike Hodges’ Get Carter screenplay.

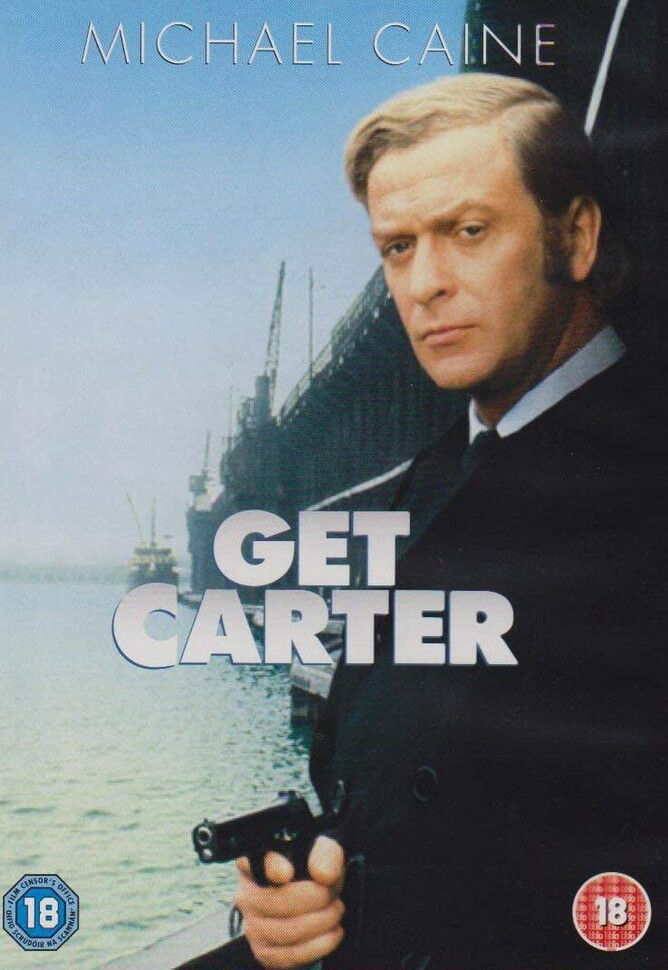

Fifty years ago this week, cinema classic GET CARTER premiered in the UK. At a Sunday night screening in Newcastle, where most of the film’s scenes had been shot the previous summer, then later the same week in London’s West End, film-goers had their first encounter with Michael Caine’s ruthless enforcer, returning to his home town to investigate his brother’s death.

Think Jack Carter and you dial up an image of Michael Caine in midnight blue mohair and Aquascutum raincoat, pints in thin glasses, Gitanes cigarettes, Ford Cortinas and big men out of shape. That train journey south to north into darkness. The pulse of Roy Budd’s theme. Carter, pill-popping, nose-dropping, soup spoon-polishing his way into cinema history with a shotgun and a bottle of whisky.

GET CARTER was adapted from Ted Lewis’s novel, Jack’s Return Home, published in February 1970, itself a landmark in British noir writing. His was a crime novel that didn’t flinch. Its characters were working class villains, inspired by, if not based on the Richardsons and the Krays and the men who worked for them. But it didn’t happen in London. Lewis’s Carter had been a Scunthorpe steel works loan enforcer.

His seamless blend of social realism and hardboiled American storytelling was exactly what GET CARTER producer, Michael Klinger, determined to produce a quality English crime thriller, had been looking for. He acquired the film rights to Jack’s Return Home and sent a proof copy to the director, Mike Hodges, in January 1970.

Hodges was more than ready to work on a big screen thriller.

Hodges was more than ready to work on a big screen thriller. He said, ‘Some years earlier I had realised the thriller – because it can so readily engage our curiosity – was a brilliant way to apply the scalpel to society.’

Originally entitled Carter’s the Name, Hodges’ script made significant structural changes to Lewis’s novel, notably cutting the Carter brothers’ backstory and removing any trace of ambiguity from Jack Carter’s fate.

For Lewis’s Humber foreshore with its disused brickworks, crumbling kilns and burned down landing stage, Hodges substituted the bleak vista of Blackhall and the colliery slag tipping into the North Sea. For the estates and terraces of Scunthorpe, he chose the dockside streets of Scotswood. Kinnear’s seedy casino, ‘White, low and ugly’ was replaced by The Heights, the house formerly owned by Vince Landa at Hamsterley, County Durham. Cliff Brumby’s ‘ranch style’ house at Burnham was the rented home of local entrepreneur and scrap metal millionaire, Charlie Newton, on the outskirts of Belmont, a newish suburb of Durham. Transposing scene after scene, aided by Lewis’s cinematic writing and meticulously thought-through plot, was fundamental to enabling Hodges to shoot at speed.

The novel had given Hodges an exceptional, complex character and an uncompromising, truthful story with which to work. Hodges gave Michael Caine a vision, a script and a backdrop which, though neither of them knew it, were the raw materials he needed to create a screen icon.

Caine’s Carter is violent, sadistic, and irretrievably flawed, emerging from the roll call of irredeemably damned villains that includes Bill Sikes, Pinkie Brown, Harry Fabian, and Johnny Bannion. But in Caine’s Carter, obsessive revenge and an inability to be reasoned with exceeds every other lawless, amoral protagonist who’d been before.

Reviews made much of GET CARTER's amorality.

Reviews made much of the film’s amorality. In the Observer, Carter was ‘a very unpleasant thug’, but an anti-hero you could identify with, even if he did ‘kill or screw’ everything that moved. In the Evening News, Felix Barker condemned the film as a ‘revolting, bestial, horribly violent piece of cinema.’ But in a week where the other main commercial release was Love Story, George Melly, for whom Ted Lewis had once played piano in a jazz gig in Hull, likened GET CARTER to a bottle of neat gin swallowed before breakfast. ‘It's intoxicating all right, but it'll do you no good.’

What few, if any critics, saw was GET CARTER as commentary on the state of the nation, the corruption taking root in provincial cities, or that it captured a sense of the national mood, as Hodges had intended.

Largely unheralded – the film was shown in a heavily censored version on London Weekend Television in 1976 and 1980 and didn’t appear on the BBC until 1986 – the reappraisal of GET CARTER began as the British cultural resurgence of the 1990s reengaged with much that the previous decade had written-off. Films wearing their working class influence found mainstream audiences.

Speaking to Crime Time magazine in 1997, Mike Hodges had a sense that the film’s moment had come again, concluding that Carter may have been ‘shot dead before our eyes’ but he still goes on. ‘He is, of course, eternal; he’s on film.’ In September that year, Hodges introduced a screening of GET CARTER at the National Film Theatre in London, an event which Steve Chibnall, author of the essential Get Carter: British Film Guide, cites as the beginning of the film’s ‘formal rehabilitation’.

Since then, Hodges’ and Lewis’s revenge blueprint has been revisited countless times. Notably in 2004, Shane Meadows’ Dead Man’s Shoes, co-written by Meadows, Paddy Considine and Paul Fraser took on the gritty, social realist revenge thriller. Writing in the Guardian, Rob Mackie declared it a ‘remorseless revenge tale which starts like Mean Streets but turns into more of a Straw Dogs/Get Carter hybrid’. In 2009, Harry Brown once again casts Caine in the role of avenging angel, this time on a south London council estate.

Fifty years on, GET CARTER is acknowledged as a classic, almost unique among crime movies, with perhaps only The Long Good Friday coming close in terms of significance. It’s still a regular on the TV schedules.

Mike Hodges’ vision, craft and determination; the ambition of Michael Klinger; the landscape of the north east, and the powerful aesthetic created by cinematographer, Wolfgang Suschitzky; an astutely assembled cast, great performances, and a memorable score go some way to establishing why GET CARTER is an exceptional piece of British cinema. A film of its time that speaks to us now, socially and politically astute, and thanks to Lewis’s novel, grounded in truth. ‘Caine is Carter’ proclaimed the film’s pre-publicity posters on London transport billboards. Fifty years on, he still is.

Nick Triplow

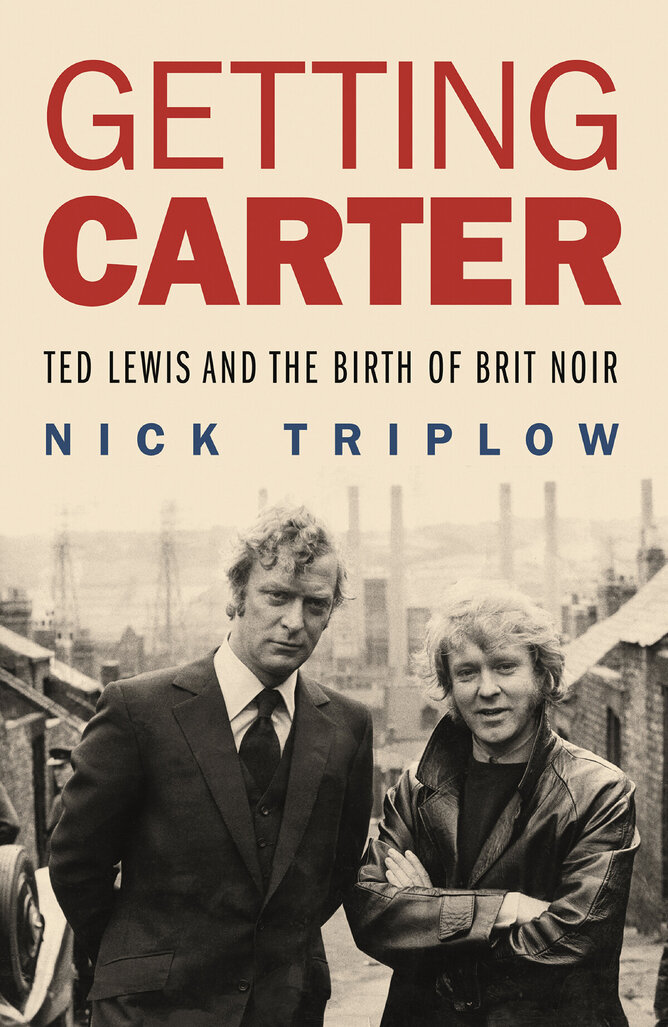

Nick Triplow is the author of Getting Carter: Ted Lewis and the Birth of Brit Noir, published by No Exit Press, which is available now in eBook and published in paperback on 20 March. Copies can be ordered via this link . Triplow is also co-organiser of the Hull Noir Crime Fiction Festival, which will be held on Saturday 20 March. Tickets to this year’s free virtual festival can be booked via hullnoir.com

© Neil Holmes